Budget Reconciliation: A Strategic Tool in Federal Lawmaking

For the last 40-plus years, lawmakers undertaking the federal budget appropriations process have looked to budget reconciliation as a fast-track procedure for pushing through their tax and policy agendas.

In 2025, President Donald Trump and a Republican-led Congress used budget reconciliation to push through their tax policy agenda and deliver on several GOP campaign promises, from sweeping deregulation to border security.

Bloomberg Government is tracking every development in the congressional budget process, with analysis on reconciliation legislation, practical guidance for lobbyists and other strategic advocates, and primers on the federal appropriations process and federal spending trends.

Our subscribers get access to breaking news, as well as accurate and up-to-date information to help policy professionals work smarter during dynamic times. Request a demo to see how our tools simplify federal budget navigation.

[Download our comprehensive Guide to Federal Budget Dynamics for an overview of the federal budget process and a breakdown of the appropriations process, legislative maneuvering, and strategic implications.]

What is budget reconciliation?

Budget reconciliation is a legislative shortcut that has become more frequently used over the last few decades in times when one party controls Congress and the White House.

The process has been used to pass sweeping measures and meaningfully transform tax and spending law. Notably, President Trump and Congress used reconciliation in 2017 to pass the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and deployed it again to make key provisions of that legislation permanent with the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” in 2025.

Budget reconciliation was created by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. It has been used by both parties to pass landmark bills and is sometimes referred to as a fast-track procedure. The process, which avoids the threat of a filibuster, requires only a simple majority in the Senate: generally 51 votes, or 50 if the vice president breaks a tie.

However, such action can come with pitfalls. For example, budget reconciliation limits the types of changes that can be made, and majority party members can fight among themselves over individual provisions, the total cost of the package, and how much it will add to the federal deficit.

How the reconciliation process works

A budget resolution provides top-line allocations for appropriations committees to guide the annual spending process. It may include reconciliation instructions or reserve funds for future bills. Per the congressional budget process and its annual timeline, budget resolutions are due by April 15 but there is no consequence for missing the deadline.

Reconciliation instructions direct committees to draft legislation to meet fiscal targets in the budget resolution. These instructions compel committees to change laws in their jurisdictions related to spending, revenue, or the debt limit with the intention of “reconciling” existing law with new fiscal priorities. These instructions often include a deadline and can require reporting of debt-ceiling legislation.

If more than one committee receives instructions, then the individual committees first send their recommendations to the House and Senate Budget committees, which consolidate the proposals. If a single committee receives instructions (for example, just the House Ways and Means Committee on a revenue measure), its recommendation can be sent directly for a floor vote.

In the Senate, debate is limited to 20 hours, meaning the measures can’t be filibustered. Proponents also need only a simple majority (51 votes) rather than the 60-vote supermajority that applies to most legislation under the chamber’s cloture rules. These details make reconciliation bills an attractive target for policy changes that have a budgetary effect, such as health-care programs.

[Download our comprehensive Guide to Federal Budget Dynamics to master the complexities of appropriations, budget reconciliation, and strategic advocacy.]

Reconciliation’s impact: legislative examples

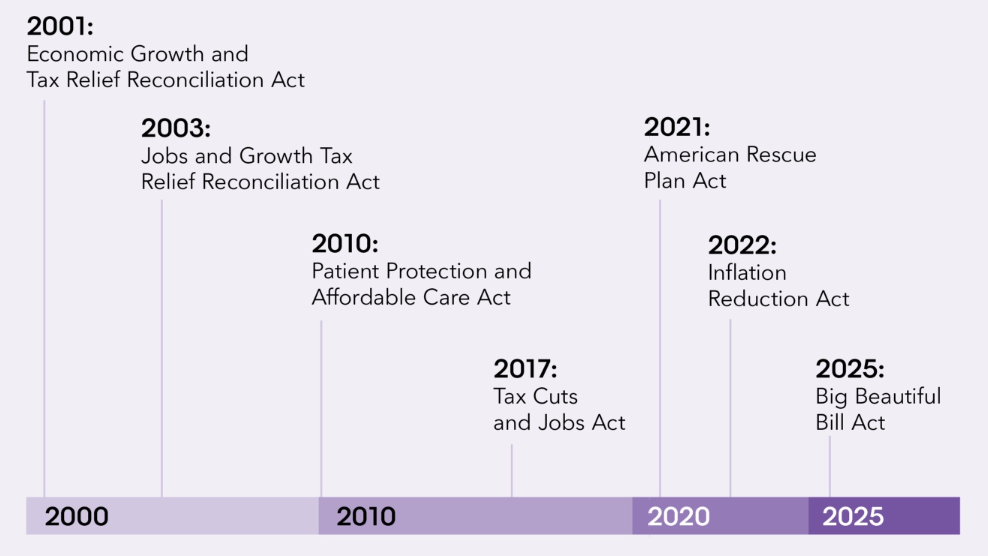

Since the first use of reconciliation in 1980, 24 reconciliation bills have been enacted into law, and four have been vetoed. Some high-impact examples of legislation passed through reconciliation include:

- 1981 – President Ronald Reagan’s reductions in welfare and food stamp benefits

- 1997 – President Bill Clinton’s expansion of the children’s health-care program

- 2001 – Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (“Bush tax cuts”)

- 2003 – Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act

- 2010 – Portions of the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”)

- 2017 – Tax Cuts & Jobs Act

- 2021 – American Rescue Plan Act

- 2022 – Inflation Reduction Act

- 2025 – One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The Byrd Rule and its constraints

In the early 1980s, reconciliation legislation often contained “provisions that were extraneous to the purpose of implementing budget resolution policies” while some committee submissions increased spending or even violated another committee’s jurisdiction, Library of Congress records show.

So, in 1985 and 1986, the Senate adopted the Byrd Rule – named after its principal sponsor, Sen. Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia. The rule was temporary at first and was modified several times before being made permanent in 1990. Of the 24 reconciliation bills enacted since 1980, actions were taken under the Byrd Rule for 20 of them, including Trump’s tax and spending bill known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill.”

Many policy professionals working today know that the Byrd Rule prohibits reconciliation bills from raising the federal deficit beyond a 10-year budget window or making changes to Social Security. But there are other important constraints of the rule to understand. According to the Library of Congress, a provision is considered to be extraneous under the Byrd Rule if it falls under one or more of six definitions:

- It does not produce a change in outlays or revenues or a change in the terms and conditions under which outlays are made or revenues are collected.

- It produces an outlay increase or revenue decrease when the instructed committee is not in compliance with its instructions.

- It is outside of the jurisdiction of the committee that submitted the title or provision for inclusion.

- It produces a change in outlays or revenues which is merely incidental to the nonbudgetary components of the provision.

- It would increase the deficit for a fiscal year beyond the “budget window” covered by the reconciliation measure.

- It recommends changes in Social Security.

Under the Byrd Rule, a senator who opposes extraneous items in a reconciliation bill can raise a point of order against it. The presiding officer decides if a point of order is sustained based on advice of the Senate’s parliamentarian. Sixty votes are required to waive the point of order and keep a provision in the reconciliation bill.

What can and can’t be included in reconciliation bills

As noted previously, the Budget Act of 1974 established points of order to explain what can and can’t be included in a reconciliation bill.

According to the Act, there are two points of order that apply in both the House and Senate:

- Amendments to reconciliation legislation cannot increase the federal deficit.

- Reconciliation legislation cannot amend the Social Security program.

And there are two points of order that apply in the Senate only:

- Items in reconciliation legislation cannot be extraneous.

- Amendments to reconciliation legislation must be germane.

How and why budget reconciliation is being used in 2025

Republicans advanced budget resolutions in both chambers early in 2025 – the first step toward enacting President Trump’s priorities through budget reconciliation, which would allow the GOP-led Congress to bypass Democratic opposition.

In February 2025, the Senate Budget Committee advanced a resolution (S. Con. Res. 7) instructing committees to craft legislation to fund President Trump’s border, defense, and energy policies, with plans to pursue a second reconciliation package focused on tax cuts later in the year.

Shortly thereafter, the House Budget Committee advanced a draft resolution setting the stage for a broader bill to include all of Trump’s priorities, with up to $4.5 trillion in tax cuts and a $4 trillion increase to the debt limit.

At that time, Trump said that he preferred “one big, beautiful bill” without ruling out a two-measure approach. House leaders said it would be difficult to pass two with the GOP’s thin majority, while Senate leaders argued the border and defense priorities are too urgent to be delayed by tax negotiations.

Both chambers must adopt the same resolution to formally begin the budget reconciliation process. This occurred in April 2025, with the Senate passing its resolution first, followed by the House a few days later.

The move cleared the way for the budget reconciliation process to officially begin. Committees were given instructions to begin drafting legislation in accordance with the resolution. Then, they reported the recommendations to their respective budget committees so that the language could be included in an omnibus bill.

After initially voting not to advance the reconciliation bill over cost concerns in May 2025, the House Budget Committee ultimately voted in favor of the bill following a weekend of negotiations in which Republican party leaders agreed to speed up cuts to Medicaid health coverage.

The House panel’s initial rejection and the resulting two-day impasse shines a light on the influence a small group of lawmakers can wield, and served as a bellwether of future obstacles and hurdles on the multitrillion-dollar fiscal package’s road to passage.

The bill eventually passed the House, but with a tight 215-214 vote and one abstention. When the legislation went to the Senate, several high-profile Republicans and Democrats pressed for extensive change.

Senate Democrats made numerous Byrd Rule challenges, leading the parliamentarian to advise that several provisions violate the chamber’s strict rules for budget reconciliation bills. This resulted in a number of changes made to the bill, and after tense negotiations and last-minute dealmaking, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed and was signed by President Trump on July 4.

[Download our comprehensive Guide to Federal Budget Dynamics to master the complexities of appropriations, budget reconciliation, and strategic advocacy.]

Strategic advocacy in a reconciliation year

Experts in law and policy say the intensity of negotiations between Congress and the White House may be attention-grabbing at times, but should not distract Hill veterans and other issues advocates from their big-picture goals.

“It’s dizzying. It can be anxiety producing and scary. But for those of us who have recalibrated our filters back to 2017, [it’s a matter of] sorting through what is going to stick and what matters,” said Rich Gold, partner at Holland & Knight and leader of the firm’s public policy and regulation group.

Gold added that the performative aspects of the congressional budget process are likely to diminish once lawmakers refocus on their end goal.

“It takes some time to adjust [to a new administration and its agenda]. But now you’re seeing things being pulled back. In 2017, the theater aspect changed over time in part because of the need to get budget reconciliation through.”

Gold recommends taking a well-rounded and circumspect approach to strategic advocacy, while also accounting for a new climate on the Hill – offering that, for example, the Trump administration’s working style is far different than his predecessor’s.

“We’re in a different type of administration… but you always have to look at advocacy from three perspectives – policy, law and communications,” he said.

So, how does Gold’s team build smart strategies and stay agile in dynamic times? For starters, they rely on modern software solutions to help them keep pace with change.

“Because of the complexity of our work, we need tech to feed our team … and we need access to the best tools [in order to] help our clients navigate the current climate and understand what their place in the market is, and then communicate that in a way that doesn’t put themselves in a vulnerable position with the administration,” Gold said.

Bloomberg Government makes it easy to track federal and state legislation and regulations, so you’ll always have the latest details to inform your strategy.

Bloomberg Government subscribers can also access CBO cost estimates, committee reports, congressional press releases, and member memos all in one place. Plus, our budget and appropriations tracker gives busy teams all they need to track bills, access summaries, monitor appropriations, and explore budget tables.

And for those who want an easy way to stay on top of budget and spending data, our Federal Funding Flow interactive diagram makes it simple to navigate the process from agency requests to enacted laws.

Our best-in-class platform helps government affairs professionals keep tabs on the federal budget appropriations process and make informed decisions leveraging the most credible sources in government news. Request a demo today.